As a history buff and screenwriter, I am always thinking of which lesser-known historical episodes could be suitable for the big or small screens. In recent years I’ve had the feeling that more and more historical events that aren’t super well-known are being used as the basis for films and TV shows. Although the market for historical films at the box office has seen a downward trend as of late, with the possible exception of the upcoming Gladiator sequel, historical TV shows have been doing well as of late. Examples include shows such as Chernobyl, Shogun (which I highly recommend) and The Spy. Recently, I was reading up on the Armenian Genocide, which I was already familiar with, but with like a lot of my reading interests, I had to dive deeper and seek the details and stories of some of the key individuals involved. This is how I stumbled upon the fascinating story of Soghomon Tehlirian, who assassinated the architect of the aforementioned genocide, Ottoman Vizier Talaat Pasha.

In case you have vaguely heard of it but do not know the specifics, the Armenian Genocide occurred during the First World War, just as the fervor of nationalism was seeping into the peripheries of Europe. Armenians had long been a prosperous merchant community within the Ottoman Empire, in a manner somewhat similar to that of European Jews. The incipient nationalism of peoples in the Ottoman lands led many Armenians to side with the fellow Christian Russian Empire in the conflict between the two behemoths in the Caucasus, although a significant number remained loyal to the Ottomans and played important roles within the government. As the Sultan was stripped of his power to govern and Turkish nationalists came to the forefront, the position of Armenians became a tenuous one. In 1913, a group of secular reformists staged a coup against the incumbent vizier and became the de facto authorities in Istanbul, headed by the three Pashas: Talaat, Enver and Djemal. They decided to enter the war on the Central Powers side, and in the chaos of the war years between 1914 and 1918 they decided the course of action. Using the pretext of Armenian volunteers fighting with the Russian Army in the area of Van (which is the large lake in the middle of the map shortly below) against Ottoman forces, the three Pashas drew up a plan to eliminate Armenians that resided close to this theater of war starting in 1915. With the multi-religious millet system that had functioned for hundreds of years collapsing, they would do as much as they could to expel Armenians from land intended for a future ethnically Turkish state. Unlike European Jews, Armenians comprised a majority in large continuous areas, concentrated in but not limited to the eastern part of modern-day Turkey. This was the mindset of the genocide’s perpetrators, in which one million and probably more Armenians were killed and many others displaced from their homeland of many millennia. Their methods were mass executions in towns and villages, along with forced marches toward Northern Syria with no food or water provided. It was the first instance of the terrifying efficiency of the modern state when it came to carrying out such nefarious goals.

Those who survived ended up primarily in Syria, Lebanon or the territory of what became the state of Armenia, which is only a north-eastern rump of what the Armenian homeland was historically. The following map provides a terrifying and clear picture of the devastation carried out by the Ottoman army and groups of Turkish and Kurdish civilians. Virtually no Armenians remained within the borders of what soon became modern-day Turkey. Furthermore, Armenia quickly came under Soviet control, and any plans to deliver national justice to the perpetrators became impractical because of the USSR’s desire to establish a friendly dynamic with the fledging Turkish state.

Every area in brown had an Armenian majority before 1915, with the orange areas having Armenian populations of between 25-50%. As of 2024, Armenians only inhabit the areas shaded in red, with the exception of a notable community in Iran (the south-east country on the map).

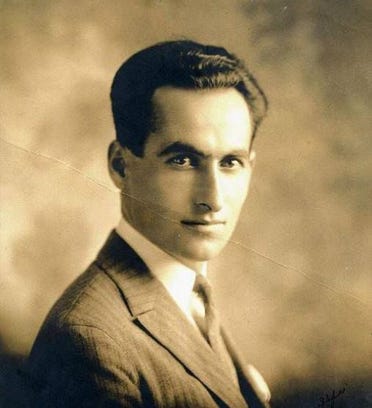

Once the war was over, the end of the empire forced Pasha into exile, so he made his way to Germany, the former Ottoman ally. In 1921, an Armenian man named Soghomon Tehlirian shot and killed Pasha with a single bullet as he was walking the streets of Berlin. After a haphazard attempt to flee, he was apprehended and taken into custody. He was then put on trial, and it seemed a foregone conclusion that he would be convicted, for two reasons. One was the fact that there were witnesses to the deed, and the second was that Talaat Pasha had been a steadfast ally of the Germans during World War I, and still had many friends in the country even after the deposition of Kaiser Wilhelm and his government. Pasha had moved into a luxurious apartment with his wife and continued his political activities from Berlin, although a court-martial established by the last Ottoman vizier had found him guilty of multiple high charges and sentenced him to death in absentia. The current German government at the time had advised Pasha that he was under threat of assassination in Germany and offered him a more secluded residence with heightened security, but he refused and had continued to agitate against the Entente powers (Britain, France, United States) that had defeated the Central powers.

The trial began and was soon the focus of intense media attention. Rather than the details of the actual murder, the emphasis was on Tehlirian’s motivations. He claimed that he was a survivor of the Turkish massacres of Armenians who had seen his father, mother, three sisters and two brothers brutally murdered in front of him. He testified that in a dream, his mother had appeared to him and chastised him for allowing her murderer to live when he had the chance to avenge her. Thus, the narrative of the trial shifted to the actions of Pasha and brought to the forefront the atrocities committed by the Turks during World War I. Tehlirian declared to the jury “I do not consider myself guilty because my conscience is clear… I have killed a man. But I am not a murderer”. While they did not use the term, the description of Tehlirian’s mental state by his defense attorneys was very reminiscent of what we now call by the name of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). He claimed to have nightmares of what he had seen during his waking hours that would occur at random intervals. The narrative was that Tehlirian had randomly come up face to face with the man responsible for ordering his family’s death, and he had acted in the heat of the moment.

After only an hour of deliberation, the jury acquitted Tehlirian. Apparently, at least some of the members of the jury had decided that his actions were justified by Talaat’s crimes against his family and nationality. The German public was shocked by the revelations of such killings of Christians committed by an ally of their country, as the press had largely avoided mentioning them, even though a few courageous German journalists and diplomats did attempt to convey the scale of what the Ottoman government was doing to its Armenian citizens. The trial was widely covered by newspapers in Europe and the U.S., such as The New York Times, The Daily Telegraph and The Chicago Daily News. German newspapers alternated between sympathy for Armenian victims and those who perceived them to be a fifth column during wartime, in the same way they perceived their country’s Jewish population. This sense of spectacle led German officials to order a speedy trial in order to avoid shining a spotlight on how much Germany knew about the genocide as it was happening. Only 9 of the 15 witnesses were heard before the verdict was pronounced, with the German government relieved that its implicit toleration of the Armenian killings was now out of the public eye.

The full truth of the circumstances of Pasha’s death and killer were not fully elucidated by the trial. In reality, Tehlirian had not witnessed his family’s deaths because he was not with them when they happened. He had moved to Serbia in 1914 to study engineering, and then volunteered for the Armenian battalions fighting with the Russian army in the Caucasus. His mother and one older brother had been murdered by the Ottoman militias in the city of Erzincan, but he did not have any sisters, and his father and other two brothers had joined the Armenian forces before the genocide had begun. This was acknowledged by his son in a 2016 interview. Tehlirian had dramatized his family’s genuine tragedy in order to give the jury a more compelling story, one that would help his case for acquittal and also make them empathize with the cause of the Armenian people.

The fact that he had crossed paths with Talaat in Berlin was also no case of serendipity. Tehlirian was a member of the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (ARF), a political party that used violent means of resistance in their quest for sovereignty for Armenians since before World War I. He had already carried out an assassination of an Armenian traitor in 1921 who had sold out Armenian intellectuals at the start of the genocide, and he was in Berlin with orders to kill Pasha. In addition, Tehlirian was told not to run away after the deed was done. The reason for this was a bigger plan to expose the atrocities that had transpired through the spectacle of a trial. The fact that Talaat was in Germany, which had closely advised the Ottoman regime throughout the war and even before, was even more poignant to the publicity sought by the ARF. They hoped to draw the world’s attention to the plight of their nation through Tehlirian’s testimony, embellished as it was, and for the most part they succeeded. It is not clear if this was his idea, or whether ARF leaders came up with the plan and told him to go with it. The whole affair was almost like a test case for a moral principle, as opposed to the usual use of trying to get a clearer picture of a law’s scope.

I’ve used the term genocide throughout this post because it is widely agreed that the actions of those in control of the Ottoman government amounted to such a charge. However, at the time of Tehlirian’s trial the word genocide was not used to describe the Ottoman massacres. The word holocaust, which means “whole-burn sacrifice” in Greek, began to be used after an American missionary used it to describe the burning of Armenians inside a church in the Ottoman town of Urfa in 1895. It is a tragic fact that the term was already being used 20 years before Talaat’s order of a total extermination, and further shows why Ottoman Armenians already had reasons to distrust their government and support the ARF. It remained the preferred term for what had happened to Ottoman Christians during World War I until Polish Jewish lawyer Raphael Lemkin popularized the word genocide in 1944. In his memoirs, he mentioned how Tehlirian’s trial led him to consider that the question of whether a government possessed the right to murder millions of people became more important than his worries about the dangers of vigilante justice and revenge. Lemkin dedicated the rest of his life to drafting and lobbying for the adoption of an international convention that would bind nations to prevent and punish actions that fit the description of genocide. Large portions of the 1948 UN Genocide Convention were based on his writings.

After the trial, Tehlirian was deported from Germany and lived a civilian life. By most accounts, he was not very ideological and considered the assassination his final duty for the Armenian people and his family. The ARF’s mission happened to be one that he felt a calling to do, but afterward he did not continue as an active member of the organization, which now drummed up support in the diaspora for an independent Armenia. He went back to Serbia, where he established a coffee business for many years, until it was expropriated by the Communists. He married, had children and eventually moved to California, where he occasionally gave speeches to crowds of Armenian-Americans and died in 1960. On the other hand, Talaat Pasha’s remains were repatriated by Nazi Germany in 1943, which was hoping to gain Turkish goodwill during World War II.

In the process of researching for this post, I read a lot of relevant and tangentially-relevant information about the situation of Armenians in the waning days of the Ottoman Empire: the failed diplomacy of Western nations, the heroic courage of Armenian military and political leaders, and the efforts of Turkish authorities to erase traces of Armenian heritage throughout their former homeland. I hope to read Operation Nemesis, a book about how the plan to assassinate the masterminds of the genocide unfolded, written by Eric Bogosian (Succession’s Gil Eavis). From the cursory overview that I’ve done, I believe there are other parts of this tragic period that deserve to be better-known, both for their historical interest and the lessons they might hold for the future.

Somebody needs to make a movie of this trial. First of all, the back-story and reveal of Tehlirian’s motive and pre-meditation make for an excellent story, rife with moral contradictions and different potential interpretations that remain relevant to this day. Was the German legal system proven ineffective by the acquittal? Was Tehlirian a hero, or a murdering liar who never experienced the genocide with his own eyes? It is also quite well-suited to the form of a courtroom drama, with the possibility of chilling flash-backs of the Armenian Genocide (albeit some of the scenes with Tehlirian would later be revealed to be false or distorted!) and the powerfully emotional journey of its protagonist. I do believe this should be a feature, even if audiences might be less likely to pay the big bucks at the movie theater to see a story they are so unfamiliar with. Most moviegoers can see any Holocaust movie and more or less go “Germans are the bad guys”, even if they are not aware of the more nuanced historical details. Whereas Turks and Armenians are not easily shoehorned into readily available mental heuristics for most moviegoers. Maybe my own passion for this riveting piece of history has eliminated the critical distance that I should use to establish what an audience would actually like and whether this is actually a worthwhile idea. Maybe so. But if done right, this could be the movie that finally brings public attention to the often-forgotten plight of Armenians, who as recently as last year were ethnically cleansed from Nagorno-Karabakh to very little global attention. The tragedies that have befallen their nation over the past century seem to confirm the sad reality of realpolitik: even allies who share a religion or meta-culture will not come to the aid of those countries that do not bring tangible material or strategic advantages along with them.

There is an elephant (or perhaps more aptly, a cow?) in the room that I have not mentioned so far, but which you could’ve possibly anticipated – what would Turkey and Turks make of such a film? The Turkish government denies the Armenian Genocide and has a long history of trying to suppress any depiction of its events in popular culture. In the 1930s, Hollywood studio bigwigs Irving Thalberg and Louis B. Mayer acquired the rights to the novel The Forty Days of Musa Dagh, which was about one of the few successful instances of successful Armenian self-defense. Despite advanced talks to produce the project and even attaching Clark Gable to star, it was ultimately never made. A significant degree of pressure was applied by Turkish Ambassador Munir Ertegun, father of Atlantic Records founder Ahmet Ertegun. A co-ordinated press campaign in Turkish media also highlighted the power Jews had over Hollywood studios and threatened reprisals at a time when Turkey had a significant Jewish population. Although the State Department presented watered-down drafts of the script, the project was dropped in the end. Subsequent attempts to make movies about the subject have either been so small that not many people outside Armenian communities saw them or were shut down whenever the ambition for a big project was there. Notably, Mel Gibson was dissuaded from filming a project about the Armenian Genocide in 2009 by a Turkish barrage of 3,000 emails to his production company. In 2017, a film titled The Promise was released, starring Christian Bale and Oscar Isaac and funded by Armenian billionaire Kirk Kerkorian. It was a love triangle set amidst the chaos of World War 1 that didn’t shy away from portraying the horrors of the genocide. While it was the first real attempt at a global film dealing with the subject, it was a box office disappointment and not liked by critics very much. I do think that these tragic events remain poorly known and could be educating for many people, especially by shining a light on Tehlirian’s actions. I’m sure the Turks would fight back against the making of such a movie, but maybe going up against these forces is the courage we should demand of our artists.

If you are interested in learning more about these events, please go to the following sources:

https://digitalcommons.usf.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1594&context=gsp

https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/210603681.pdf

Justifying Genocide: Germany and the Armenians from Bismarck to Hitler by Stefan Ihrig

https://agmipublications.asnet.am/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/IJAGS_Vol._5_N1_67-89.pdf